[ezcol_2third]In 1812 the Hudson's Bay Company gave Lord Selkirk a land grant of 116,000 acres centred on the junction of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers in the Red River Valley to bring in Scottish settlers. The Métis opposed the settlers because they feared losing their lands, since they were squatters and held no legal title. Many Métis were working as fur traders with both the North West Company and the Hudson's Bay Company. Others were working as free traders, or buffalo hunters supplying pemmican to the fur trade. They had settled along the Red and Assiniboine Rivers, with their homes along the river, and long narrow lots extending back from the river in the French Canadian style. But they had no legal title to their land, even though they had occupied it for some time. The Hudson's Bay Company wanted to stop Métis from selling pemmican to the Northwest Company, and the settlers tried to stop the Métis pemmican export business because they wanted the pemmican for themselves. Miles Macdonnell, leader of the settlers, passed a law to stop the export of pemmican from the district. Métis, led by Cuthbert Grant, ignored the new law. There was constant conflict between the Métis and the settlers. At a confrontation with the Métis at Seven Oaks in 1816, 21 settlers were killed. This became known as the Seven Oaks Massacre.

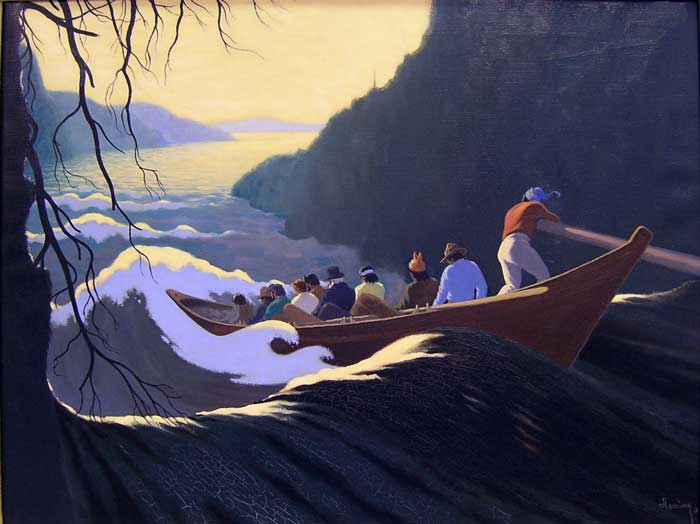

The Hudson's Bay Company tried to monopolize the fur trade by outlawing all other traders. But the Métis were the majority in all the settlements, and refused to comply. The Hudson's Bay Company needed the Métis, so it finally made compromises. During the 1850's, the Métis succeeded in breaking the fur trade monopoly that the Company had held until then, and they gained some political and property rights. But their old way of life was disappearing. The buffalo were declining in number, and the Métis and First Nations had to go further and further west to hunt them. In 1857 the Dawson-Hind exploration expedition arrived from eastern Canada to study the land. The expedition recommended that the Canadian government acquire the arable part of the Company's land for settlement. At the same time, many Americans were pressing Washington to annex the Hudson's Bay Company lands. The Company had no way to defend its lands in case of an American invasion. As well, profits from the fur trade were declining because the Hudson's Bay Company had to extend its reach further and further away from its main posts to get furs. The York Boat (by Arthur Heming) with which many Métis, in the employ of the Hudson's Bay Company, ferried fur and trade goods all over western and northern Canada. In 1869, the Hudson's Bay Company agreed to sell its territory to the new Dominion of Canada, which had been formed in 1867 by the uniting of four British colonies:Canada East (Quebec), Canada West (Ontario), New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia. First Nations were alarmed when they heard rumors that the Hudson's Bay Company was selling their land (i.e. the First Nations' land) to the new government of Canada in Ottawa. The Métis were also alarmed. They feared they would lose their lands and their rights. They were especially alarmed that no one was consulting them about the takeover by the government of Canada.

[/ezcol_2third]

[ezcol_2third]____

Francis Caldwell has published hundreds of magazine articles and 10 books. Awards include the prestigious Enos Bradner Award, the Northwest Outdoor Writers Association's highest award for outstanding journalism, Several 1st place awards for Excellence in Craft from the Outdoor Writers Association of America and the Northwest Outdoor Writers Association.[/ezcol_2third]

[ezcol_2third]

After serving in the Navy during WW II he resolved to never go to sea again, then spent forty years on boats in Alaska. Francis moved to Ketchikan in 1950, when Alaska was still a Territory, and lived in Ketchikan and Sitka a total of seventeen years. Mr. Caldwell has traveled almost everywhere in the state, from Point Barrow to the Alaska Peninsula. Now that he's "swallowed the anchor", he hangs out in Port Angeles. That's about as close to Alaska as he can get without actually being there.

Fresh out of high school, I served a hitch n board ships in the Navy. The war with Japan ended while I was on LST 270, between Midway Island and Japan, part of a secondary, back- up convoy in case the first invasion intending to strike the Japanese homeland was unsuccessful. Atomic bombs ended the war.

When we returned to Hawaii, we encountered a typhoon that nearly sank us, and actually broke welds in the hull. One ship in our convoy sank. It was a bitter lesson how cruel the sea can be. In Pearl Harbor we picked up five hundred soldiers and marines, all weary veterans of many battles, who had spent several years overseas.

Now that the war had ended, they’d been paid and were headed home, destined for discharge. With our human cargo sleeping on cots in the hold, and anywhere we could find room for them, we set sail for the mouth of the Columbia River. Our 320-foot-long ship was hard-pressed to feed such a large number of men, and the chow lines were nearly continual. There was a lot of griping. Men who had lived for days on K-rations complained about eating rice and beans. Although gambling was illegal, a poker game started in one of the compartments forward of the crew quarters as soon as we left Pearl Harbor. It continued night and day, and never stopped until we reached the Pacific Coast. The officers knew about it, but avoided that part of the ship. Several times I walked by and saw an estimated $5,000 in cash on the table.

Thick fog engulfed the coast as we approached the Columbia River Lightship. The vessel’s rails and gun tubs were crowded with men anxious to get their first glimpse of the United States. With the loud, mournful blast of the lightship’s fog horn in the distance, the fog lifted momentarily.

We were amazed to discover our ship surrounded by a large fleet of tiny fishing craft. Long, slender poles stuck out sideways; the boats resembled Water Striders. Men working in the stern waved as we passed. A very heavy ground swell was running and the little boats bobbed up and down like ducks, occasionally disappearing behind an enormous swell.

No one on board had ever been to the Oregon Coast before. What the boats were called, or what they were fishing for, remained a mystery, until we passed very close to...."